Scientist Rebellion: Hunger

This is the fourth of a series of blog posts that I am writing during the Global Scientist Rebellion, March 25th-28th 2021

My Experience and Reflection on Fasting

The first day of fasting was difficult to notice too much. I was a bit hungry, but the goal of fasting for three days as part of a global movement was more than motivating enough that I didn’t worry about not eating or feel a great urge to break my fast.

Day two started off much the same, with feelings of why did I ever bother eating in the first place, I feel fine. Going for a walk in the afternoon I noticed that I had become tired and slow, and as the afternoon turned to evening I was increasingly sensing dull aches across my body, the occasional rumble of my stomach, a fatigue and dizziness.

This morning begins my third full day of fasting, and I feel similar to yesterday, except with an unsettled and aching stomach.

Over the past few days, I have had time to reflect on my usual diet - almost always three good meals per day. What would a more natural diet consist of? Paleolithic hunter gatherers who lived from approximately 2.5 million BCE until ten thousand BCE were used to foraging over periods of scarcity. They likely wouldn’t have cooked any of their food. They were also biologically different to us. I don’t really know much more about their diet than that.

But there is no need to imagine such distant different people to understand food scarcity. In the UK, the Trussel Trust was reporting record high levels of foodbank use before the pandemic. Since then there has been a 61% rise in foodbank use in the UK1. Foodbanks provide emergency food and support for people locked into poverty. They do an incredible job of supporting our most vulnerable. But they shouldn’t exist, there should be no food poverty.

Foodparcels delivered by School Food Matters, one of the charities partnered with UNICEF during its first ever domestic emergency response programme to provide food support for vulnerable children in the UK - source: sky news

The Trussel Trust is the UK’s biggest foodbank charity, supporting 2/3 of the nation’s 1800 foodbanks. Emma Revie, chief executive, made a statement on their covid-19 response:

Communities throughout the country have shown enormous resilience in helping more people than ever before. But food banks and other community charities cannot continue to pick up the pieces. None of us should need a charity’s help to put food on the table.

Our research finds that Covid-19 has led to tens of thousands of new people needing to use a food bank for the first time. This is not right. If we don’t take action now, there will be further catastrophic rises in poverty in the future.

But it doesn’t have to be like this. The pandemic has exposed the power of what happens when we stand together in the face of adversity. We must harness this power to create the changes needed to prevent many more people being locked into poverty this winter.

Food poverty in the UK is a political choice made by the Conservative party. The Trussel Trust recommended last September that the government protect incomes by locking in the £20 rise to universal credit brought in at the start of the pandemic (the threat of losing £1,000 a year still hangs over six million families). They asked that the government suspend cruel benefit debt deductions and make local safety nets stronger by investing in local welfare. The UK government failed to do this too.

The UK government hasn’t only caused an increase in hunger and food poverty in the UK. By cutting international aid during a global pandemic, they have ripped away resources from communities who need them now more than ever.

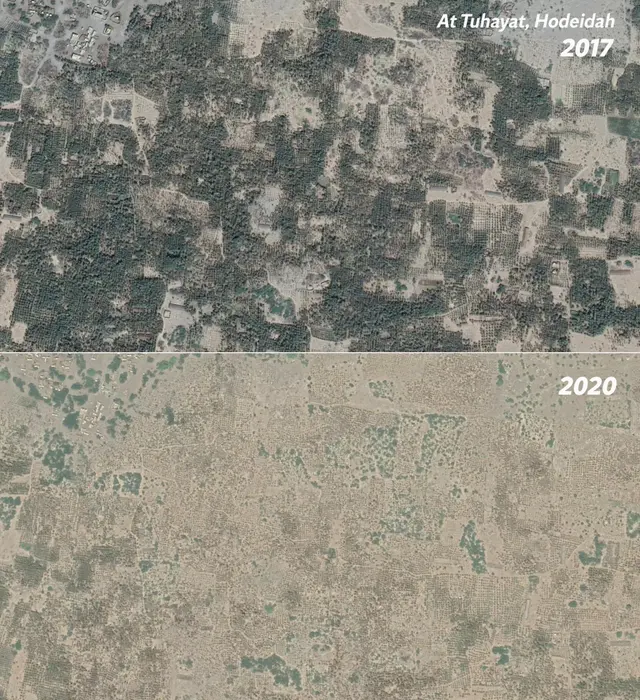

Satellite imagery shows dying date palms in Hodeidah, whilst war rages in Yemen - source: Independent

British MP Zara Sultana yesterday reported the “very British scandal” of manufacturing weapons to be used against the Yemeni people2, six years into a war that has taken the lives of hundreds of thousands, and seen millions facing starvation.

Our government is complicit in this, yet the topic of hunger is rarely covered in British media. Why?

Fasting has helped me reflect on these issues, and empathise with those facing hunger. I have fasted in relatively easy conditions - an end in sight, mild temperatures, I don’t need to be fit and able to work in factories or fields to ensure my income. I have water available to me at the turn of a tap, and shelter to keep me warm.

The UN sustainable development goals3 have been developed to tackle issues including poverty, hunger, equality, health. The original aim was to achieve this globally by 2030. Yet according to the UN, the world was offtrack to meet these targets before the pandemic4.

If we seriously want to tackle these issues, it requires much greater action, and support from countries such as the UK. It means economies whose goals are no longer driven by endless growth and the accumulation of private wealth. It means a new society based on democracy and collective ownership, entrusting more power into workers so that production can meet the needs of the many.

We must demonstrate real solidarity and prioritise human wellbeing, sustainability, and rapid decarbonisation.

This won’t be achieved with neoliberal economics (our current economic system of class division and exploitation). We must start a revolution - grounded in peace, justice, and a shared knowledge that we want a better future for our shared planet.